Michael Pisaro - Étant donnés (CD)

SKU:

$14.00

$11.00

$11.00

On Sale

Unavailable

per item

GW 014

CD inside a cardboard folder with liner notes by Michael Pisaro, transparent plastic cover.

|

TRACK LIST

1. give me your sines (2:44) 2. rounds most pinched, most arched (10:00) 3. bass never smiles (4:04) 4. sympathy for 11 (11:00) 5. escape from new chords (6:24) 6. shosty riot (5:34) (released February 5, 2018) CREDITS

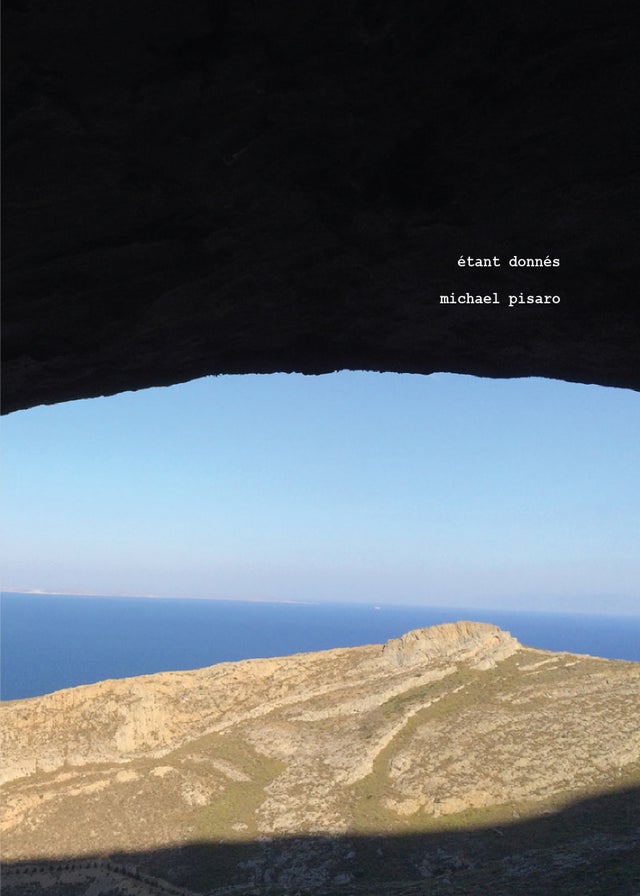

Étant donnés [2015-2017] 1. give me your sines (2’44) 2. rounds most pinched, most arched (10’00) 3. bass never smiles (4’04) 4. sympathy for 11 (11’00) 5. escape from new chords (6’24) 6. shosty riot (5’34) compositions based on samples by Michael Pisaro cover photo of Pherecydes’ Cave, Syros, Greece by Michael Pisaro inside image by Michael Pisaro produced and designed by Yuko Zama |

Étant donnés (GW 014) is a six-track disc based almost entirely on samples.

1. give me your sines (2’44) 2. rounds most pinched, most arched (10’00) 3. bass never smiles (4’04) 4. sympathy for 11 (11’00) 5. escape from new chords (6’24) 6. shosty riot (5’34) REVIEWS

Michele Palozzo, esoteros What do the volcanic genius of Marcel Duchamp’s anti-art and the American master of “quiet composition” Michael Pisaro have in common? Until now the only obvious missing link between the two was undoubtedly represented by the multifaceted intellectual and artistic figure of John Cage, admirer and chess companion of the irreverent French Dadaist. Now the title of the last environmental installation left by Duchamp to posterity – jealously guarded by the Philadelphia Museum of Art together with the Grand Verre and many other works of his – resounds next to Shades of Eternal Night in Pisaro’s dual return to his own Gravity Wave label after a three-years long pause. Étant donnés was an ultimate coup de théatre elaborated secretly over twenty years, consisting of a wooden door through which you can see a sort of three-dimensional diorama, an illusory landscape dominated by a provocative naked woman spreading her legs. Once again, the main goal was to desecrate in order to achieve another type of sublime, exclusive and absolute, devoted to nobody, let alone the wicked art market/ system. Except that here Pisaro’s procedure is reversed – Warholian but not serialized – starting from the humble in search of his possible, unprecedented ennobling. The peculiar audio excerpts and samples selected by Pisaro are his étant donnés, the initial data to elaborate the resolution of a problem, typically of a mathematical or scientific nature. Fragments of ignored music, probably snubbed outside of a few fans of their respective genres: soundtracks for B-movies or night-time projections, such as the blaxploitation “Superfly” music by Curtis Mayfield (“give me your sines” and “bass never smiles “) or “Escape from New York “by John Carpenter (“escape from new chords “), a sound that, referring directly to the generations of analog supports, evokes the rustling and audiovisual distortion of videotapes and local television networks, along with the solitude of idle evenings. Considering his previous production, at first it is difficult to believe that the American composer let himself be seduced by a project that apparently divides itself between the serious and the facetious: however, it is curious – and subtly fascinating – how from the combination of 80’s sounds and short waves not a striking contrast arises but something new, somehow foreign to both domains. By means of the juxtaposition of a discreet and purely minimal factor, Pisaro appropriates without effort the persuasive groove that inaugurates the album and a shining symphonic crescendo by Shostakovich, “invaded” by the Pussy Riot punk which seals it (“shosty riot”), thus crossed by a neutral element that compresses the effect, extends their perspective point to make them absolute sound phenomena, free from a precise historical and cultural connotation. Instead it’s the apparent emptiness, represented by an almost imperceptible background hum – the shadow of a feedback – that gives intensity to the few melancholic guitar chords that interrupt it, whose reverberation expands in the same boundless absence that generated them. Its possible continuation comes with “sympathy for eleven” (the title, indicating its exact duration, is a parody of the Rolling Stones): a Zen garden where continuous, gong-like tones and variations of the six strings resonate on a single note, before the muffled entry of an orchestral elevation in slow motion, thus smoothed out in its details and reduced to a dense polychrome nuance. Anything but a trivial project, the essence of Étant donnés is elusive and can remain completely invisible to the distracted listener: nevertheless, the work does not require a particular interpretative effort, but only a predisposition – be it innate or acquired – to accept expressive ways out of the ordinary, enigmatic and even impervious ones. The poetry hidden in Michael Pisaro’s sound can’t be accessed through any shortcut, but your dedication will not fail to be repaid. (1/1/2020) Ed Howard, reddy brown objects Michael Pisaro’s Gravity Wave label has been dormant since the release of 2014’s 3-disc Continuum Unbound set, although the composer’s prolific output has hardly slowed in the intervening years. Nevertheless, this year finds him reviving his own imprint starting with a pair of fantastic, contrasting new albums. Étant donnés is the odder of the two, a seeming outlier in the composer’s catalogue, but only on the surface. Viewed from another angle, the fascinating thing about it is how much it reveals about Pisaro’s core aesthetic. By applying his familiar techniques to unexpected materials, this disc provides an especially clear window into the structures and processes that form the heart of Pisaro’s body of work. Both of these recent discs (the other is called Shades of Eternal Night) have been in gestation for several years during Gravity Wave’s hiatus, and both are directly inspired by works of visual art. Étant donnés borrows its name from Marcel Duchamp’s final work, an unsettling diorama completed in secret over the course of two decades while he was publicly retired from art. The connection suggests a music assembled from assorted bric-a-brac, meticulously crafting something elaborate and beautiful/strange from the most ordinary raw materials. The song titles suggest another connection, to Duchamp’s descendants in Plunderphonics music: goofy half-puns like “Give Me Your Sines,” “Sympathy for 11,” or “Escape from New Chords” could be slotted into a KLF tracklist without fuss. A few pieces here make mischievous nods in that direction, but Pisaro mostly takes Duchamp’s post-modern encouragement to make art out of other art, or other sources, in very different directions. As I’ve been hinting, samples are the primary building block here. Pisaro has of course often sampled in his work – from raw material prepared by his collaborators or from field recordings – but here he draws his samples mostly from commercially available music, and does little to hide it. Two of the album’s defining tracks – “Give Me Your Sines” and “Bass Never Smiles” – sample liberally from Curtis Mayfield’s SuperFly soundtrack. On “Escape from New Chords,” probably the most straightforward track here, Pisaro slows down John Carpenter’s score to Escape from New York into a funereal dirge, its buoyant synthesized fanfares eventually sputtering out into low bassy moans and electronic warbles. Album closer “Shosty Riot” interpolates Shostakovich with snippets of punk rock. This is new territory for Pisaro, and it’s exciting both for its novelty and for the playfulness with which he leaps into this material, but he also makes the new approach fully his own. The album opens with Pisaro sampling and looping a tiny fragment of the bass-and-drums intro to Mayfield’s “Give Me Your Love,” suspending a ringing sine tone over the skeletal groove. It’s an exercise in tension and restraint, the tone gradually becoming more insistent until finally the groove’s minimalism relents, allowing in little firework bursts of piano chords and Mayfield’s chiming guitar as the drums accelerate to a rolling crescendo. It’s lovely, building this exquisite miniature groove out of just a few elements carefully sliced out of the original song. Meanwhile, the electronic tone seems to hover above the rest of the music. It never blends in, and the underlying groove sounds muted, washed-out in comparison to this crystalline clarity. Pisaro simply presents these two separate strands side by side, allowing them to coexist without really intertwining – it recalls, oddly enough, the relationship between sine waves and field recordings on his Transparent City albums. “Bass Never Smiles” is both more radical and the most delightful piece on the album. Another brief track, this one deconstructs Mayfield’s “Little Child Runnin’ Wild.” For much of its length, the sampled music forms a barely heard backbone, its pulse translated into whistling sine wave rhythms, little blips of the underlying music cracking through as momentary glitches. There’s a brief catharsis in the form of a bracingly loud electric guitar loop, and then the track’s second half alternates snatches of Mayfield’s singing with high-register electric squiggles and a muted bassline that faintly maintains the throughline to the original track. It’s playful and affecting, and particularly on “Bass Never Smiles” Pisaro maintains a delicate balance between nostalgic homage and creating something new from his source material. The really striking thing, though, is the kinship between Pisaro’s approach here and his other music. Many of his previous compositions have taken simple, granular sounds as raw materials, building blocks to be arranged into larger constructions through a combination of the composer’s parameters and the performer’s choices. On this album’s sister work, Shades of Eternal Night, piano chords played by Reinier van Houdt are sampled, electronically processed, and arranged into dense, reverberating clouds. As different as the two albums are in mood and style, hearing them together reinforces this continuity in Pisaro’s work. So many of his pieces revolve around a sublime tension: modular, piecemeal construction leading to music that flows and crests in waves of sounds, or in wave-like alternations of drone and silence. On Étant donnés, the modules are often blocks of sound borrowed from other artists, but the way Pisaro works with them, the primacy he gives to spatial relationships between sounds – even if, as here, they’re only artificial relationships conjured in a virtual electronic space – makes this disc fit comfortably with his other work. The shorter sample-driven tracks here are interspersed between two longer pieces on which the samples, though presumably still forming the foundation of the music, are less overt. “Rounds Most Pinched, Most Arched” is precisely 10 minutes of humming ambience, with barely audible teases of melody deeply submerged within the hushed electronic fog. At intervals (probably timed out in the score given Pisaro’s past working methods) this hissing backdrop is interrupted by a chiming drone that might be a slowed-down guitar, mournful and beautiful, its contours hinting at a familiar melody but (at least for me) never quite resolving to reveal its source. “Sympathy for 11” is likely another time-based Pisaro score, clocking in at exactly 11 minutes. It is similarly droning and minimalist, built on a foundation of subterranean hiss and feedback hum, with bright, spacious electric guitar lines that recall Pisaro’s own playing. This is more active than “Rounds,” with sampled percussion providing slow, clumsy beats at times, but each guitar chord is still left room to deteriorate and fade. The piece’s second half builds melody from an ambient haze, utterly obscuring possible source material. The album closes with its oddest track, “Shosty Riot,” built around samples of the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich: martial, pounding drums looped and processed into a trashcan industrial rhythm; strings stretched into melancholy drones; orchestral fanfares that give way to garbled, sped-up chipmunk punk rock. It’s chaotic, some of the most abrasive and deliberately grating music Pisaro has made, and yet even here there’s a sense that everything is in its right place. In some respects, this album’s namesake seems a strange choice for Pisaro. Duchamp’s eerie final work, with its voyeurism and its ambiguously sinister undertones, doesn’t really seem to resonate with the tone of Pisaro’s music, even on this for him unusual project. I wonder if what Pisaro responds to is not so much the content of the piece as its means of construction: a landscape assembled from bits of detritus and varied textures, a backdrop stitched together from photographs and painting, everything carefully laid out just so over the course of years, within a 3D space where there’s a complex interplay between the different layers of the piece. It’s in this sense that Duchamp’s work seems like an appropriate analogue for the multilayered sound spaces Pisaro constructs from these borrowed sounds. (2/26/2018) Bill Meyer, Dusted On the face of things, not much connects Michael Pisaro’s Étant Donnés with its namesake. Marcel Duchamp did his final work in secret over the course of 20 years, during which time he let the world think that he had given up art to become a professional chess player. Per his instructions, the work was not shown until after his death. Pisaro, on the other hand, is in a publicly productive phase of his own career as a composer, instructor, improviser and guitar player. His music is being performed on several continents, and the two and a half year gap between the release of these two CDs and their predecessor on his Gravity Wave imprint has been more than made up for by albums on other labels. Moving beyond the circumstantial, Pisaro’s Étant Donnés is by turns playful and exquisitely turned, with none of the lurid impact of Duchamps’ exposition of voyeruism. But just as Duchamp’s subtitles invite the viewer to look beyond the splayed female body in the foreground, Pisaro’s record shows you that surface impressions do not tell all. While Pisaro is best known for exploratory work that uses suggestive texts, time prescriptions, field recordings and improvisation to convey his own intentions and to elicit contributions from other music makers. On this album’s six tracks, he applies similar methods to highly recognizable samples. “Escape From New Chords” makes mincemeat of its title by putting a dragging thumb down upon a particularly gaudy passage form a John Carpenter soundtrack. There’s no getting out, but there are some lovely things to hear once you quiet down and hold still. “Shosty Riot” likewise takes the air out of some heroic, martial poses by Dmitri Shostakovich and hands the last word to Pussy Riot. Two other tracks refract Curtis Mayfield grooves through a sparingly dub-wise prism. While the two time-bound tracks are less obvious about their sources, their titles offer hints about their essence. “Rounds Most Pinched, Most Arched” lasts exactly ten minutes, and it sounds as though it was constructed from curving phrases that were pinched from another century. And if “Sympathy for the Devil” proclaimed the indivisibility of humankind and Lucifer, might the wavering electronic tones, ascending orchestral strings and stark electric guitar chords of the precisely 11 minute-long “Sympathy for 11” be telling us that time as we know it is a human construct? It may be worth noting that Pisaro’s work often references poetry. To grasp a poem’s essence, the reader may have to meet it halfway. Likewise it’s up to the listener to divine meaning from dissection and abstraction expressed by Étant Donnés. (5/10/2018) |