- Jürg Frey

- >

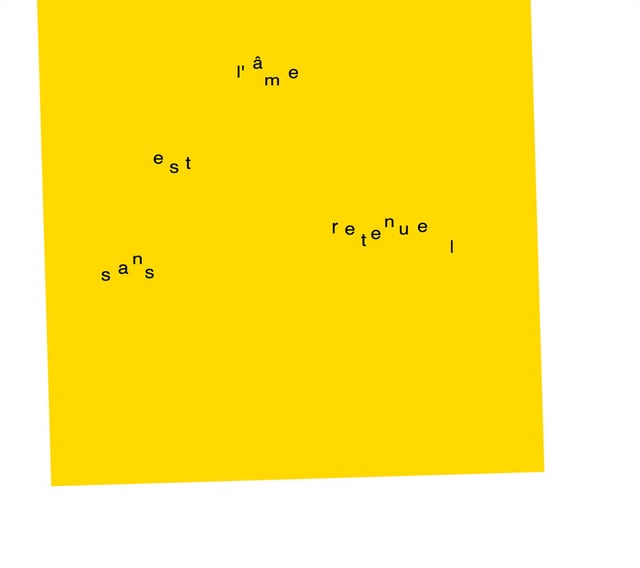

- Jürg Frey - l'àme est sans retenue I (5CD)

Jürg Frey - l'àme est sans retenue I (5CD)

SKU:

$42.00

$42.00

Unavailable

per item

ErstClass 002-5

A massive work from composer Jurg Frey focused on the dynamic relationship between sound and silence, and how it can affect our perception of the silence in a frame of space and time, using environmental sounds of field recordings and silence to create a massive work over six hours, modifying pitch, rhythm, dynamics, texture, and overtone, here properly released on 5 CDs. 10-panel package, liner notes essay and cover art by Jürg Frey, design by Yuko Zama.

For lossless (16/44) files, go to this page.

|

TRACK LIST

Disc 1 1. (01:13:42) Disc 2 1. (01:13:41) Disc 3 1. (1:13:52) Disc 4 1. (1:13:52) Disc 5 1. (1:04:52) (released October 6, 2017) CREDITS

field recordings by Jürg Frey in Berlin, October-December 1997 composed and mixed by Jürg Frey in Aarau, Switzerland in 1998 mastered by Taku Unami design by Yuko Zama cover art inspired by Jürg Frey-Stück (1974) #36 produced by Yuko Zama and Jon Abbey |

Swiss composer Jürg Frey's six hour long electronic tape piece l'àme est sans retenue I was recorded and assembled in 1997/98 and is now being released for the first time. It is the longest piece Frey has ever composed in his over 40 year career.

In this piece, Frey utilized the sounds of field recordings he made in Berlin in 1997 as the source materials, alternately inserted between long stretches of silence. Frey was particularly focusing around that time on how the dynamic relation between sound and silence can affect our perception of the silence in a frame of space and time. By using the environmental sounds of field recordings and silence as materials, which was an unusual method of composing music at that time, Frey created a subtle but captivating flow over the six hours in which nearly imperceptible pitches, rhythms, dynamics, textures, overtone - all emanating from the natural environment - are faintly consonant with each other. "It's about how 'normal', 'regular' things are transformed - by the work of composing, by decisions, by intuition, by the ear - to an art work." (Jürg Frey) The title "L'àme est sans retenue" is a quotation of a single, isolated sentence from French poet and writer Edmond Jabès's book Désir d'un commencement, Angoisse d'une seule fin (Desire for a Beginning, Dread of One Single End). The simple clear-cut structure and slightly enigmatic, ambiguous air of Frey's l'àme est sans retenue I echo with the world of Jabès's book, in which a large portion of white space (silence) is distinctly present between blocks of sentences and a list of evocative keywords create introspective, silent, distant atmosphere. REVIEWS

Michele Palozzo, esoteros The classics according to Erstwhile Records: home to the most radical improvisation projects, last year Jon Abbey’s label started its first anthology series devoted to contemporary composition. A trail already explored by the now ten-year-old Another Timbre owned by Simon Reynell, although in the variety of the American label’s catalogue it seems to take on an even greater officiality. Significantly enough, the first authors represented and tributed by ErstClass both belong to the international Wandelweiser collective: the “composers of quiet” (Alex Ross) devoted to the exploration of pure and near-silent sound shapes, are some of the bravest and radical figures in contemporary experimental music, whom now finally and deservedly emerged from the shadow thanks to the contribution of said independent labels. Last year, the founding stone was Michael Pisaro’s oeuvre for solo piano (“The Earth and the Sky“, 2016), performed by the loyal Reinier van Houdt. Even more impressive and of great documentary importance is the second chapter, a recovery from the archive of Swiss composer Jürg Frey, never released on record before. It is as monumental in duration as, predictably, essential in its sound aesthetic: the tapes of l’âme est sans retenue I (1997/98) last for a total of exactly six hours, much of which are occupied by an absolute artificial silence, interspersed with short patches of field recordings made in Berlin, which open and close in fade for a few seconds. The splendid paradox underlying the work as a whole is that these poorly recorded bits almost always act as “frames” for motionless open-air environments, thus creating a continuous contrast between two types of silence, both impossible: the one being a digital emptiness, uncreatable with the tools at our disposal; the other in the cagean sense, that is to say, with no sound produced intentionally but “inhabited” by chance and the intrinsic rustling of the recording medium. In fact, the most musical elements you will hear in these tracks are a church organ, a dozen meters away, and the Doppler effect of a plane crossing the sky. A work unfolding so uniformly, for a time far above the average of any genre, would seem to offer very few reading keys on top of its pure phenomenology. However, after a first phase of settling to recognize the only direction in which the work proceeds, there follows another in which the living and breathing dialogue between its basic elements becomes evident: against all expectations, there arises an authentic feeling of expectation and longing for the opening of those modest windows on reality, and if on the one hand their duration remains almost the same, it happens instead that the intervals between them will persist for entire minutes on which one experiences a vague sense of abandonment, the uncertainty of a return that we’ll reasonably define as Beckettesque. At this experiential level, the work reveals itself in its deepest meaning and can be said to be accomplished: "Silence is not uninfluenced by the sounds which were previously heard. These sounds make the silence possible by their ceasing and give it a glimmer of content. […] Silence, in its comprehensive, monolithic presence always stands as one against an infinite number of sounds or sound forms. Both stamp time and space, in that they come into appearance, in an existential sense. Together they comprise the entire complexity of life." - Jürg Frey, 1998, “Architektur der Stille”, (‘The Architecture of Silence’, translation by Michael Pisaro) Below the vast, lightly rippled surface of l’âme est sans retenue I lies an incontrovertible poetic statement, the unexpected foundation of a musical journey lasting for over forty years now: in all its exterior appearance, sound is the distinctive feature of that which exists, if briefly, immersed in the sea of the sensory experience that unites us; and like gently rising waves, Jürg Frey’s apparent achromes acquire a value that otherwise would have almost gone unnoticed, or even lost. If, during the time of your life, you’ll decide to face these hours of listening in their entirety, you too will have taken part in a battle which has always been that of Erstwhile: restoring the hegemony of “sound” on “music”, and continuing to imagine the possible declinations of an utopian art for art’s sake. —-- The title of the work [tr. “The soul is unbridled”] quotes a single phrase by French poet Edmond Jabès, drawn from the book Désir d’un commencement, Angoisse d’une seule fin (“Desire for a Beginning, Dread of One Single End”). Bill Meyer, Dusted In her book Experimental Music Since 1970, Jennie Gottschalk said that a typical piece of Wandelweiser music is “not a duration to mark, but a space to occupy.” L’Âme Est Sans Retenue I, by longtime Wandelweiser member Jürg Frey, is hardly typical, but that phrase is a handy way to start coming to terms with its vast lightness. It could fairly be said to be both. Spread across five CDs, it is exactly six hours long. But if you value spatial metaphors at all, you’ve no doubt talked about having or lacking space in your calendar, and finding that chunk of space is just one of the matters to be reckoned with as you deal with this piece. Do you play it a disc at a time, in order or out of sequence, all the way through, or on repeat? Do you listen closely, or let it play in the background or turn it into an installation that you can approach or avoid as whims and circumstances dictate? Each will yield a different impression, and that’s just one reason why this review should be taken as a set of responses rather than a last word. To some extent that’s true of any music; even the Minutemen’s “The Punchline,” which lasts just half a minute and contains just 21 highly specific words, has room for interpretation, and that can only be magnified when the work is 720 times as long. So whatever I say here should not be taken as a reason to take yourself off the hook; you ought to experience this thing someday, if only to see what it’ll do to your notions of what music is and does. The album is well represented by its packaging, a gatefold with just five elements — yellow blocks, white space, and (mostly hidden) text. Frey, who is also a clarinetist and composer, made this piece in 1998 from field recordings he made the previous year in a Berlin park. The sound elements are generally brief in duration, one to 30 seconds. They range from indistinct grey noise to information-rich passages which can be taken as portals into a city that has about as much in common with what you hear as a distant snapshot of a person taken 20 years ago has with the flesh and blood individual today. Even if they’ve kept themselves up, every living cell in their body has turned over two or three times; likewise the church bells and tree noises may be similar, but the traffic? The conversations? The sonic content abuts silences that are sometimes about as long as the sounds, but sometimes last up to ten minutes. Sometimes the boundaries are diffuse, sometimes abrupt, but even at their most defined the sounds themselves are never very loud. Put this thing on in a house with forced air heating and cooling and there are vast passages where you’ll have a hard time telling the two apart. For a partisan, post-Cage-ian audience that understands and embraces the active listener’s role in connecting with sound material, L’Âme Est Sans Retenue I (the title translates from French as “The soul is unrestrained,” and the numeral signifies that this is one in a series of similarly named compositions) might be epiphanic. Such a listener might marvel at the intensity of the quiet, the subtlety of the transitions, the texture and substance of even the most indistinct sound passages. But why confine it to the converts? Suppose people who weren’t seeking it were given the chance to hear it passively as they passed through, or to hear it at length when required to wait a spell. Imagine the effect it might have in an office building foyer, or a mall, or playing in speakers spread around a park? Imagine how it might be received by callers who are on hold, or by people in a waiting room. Imagine how the mere specifics of the piece might rattle someone’s notion of what you can make music from, what it can sound like, or how long it can last? For some it could be an unlocking key that opens up new information about the sonic and temporal spaces we pass through, and for others, news that the lock and key exist. Joshua Minsoo Kim, Tone Glow Across the six hours that comprise l'âme est sans retenue I, Jürg Frey presents a carefully considered assemblage of field recordings and silence. The organizational structure of the piece is simple and austere: field recordings fade in, are left to simply exist, and then fade out into silence. Both of these elements span approximately ten to thirty seconds and this alternation occurs until a longer period of silence emerges. In the long tradition of Wandelweiser, Frey's arrangement makes an irrefutable case for the importance of silence in composition. And as with countless other works, this privileging of silence as compositional material allows for a consideration of our listening environment as a wellspring of its own musical details. The field recordings that appear on l'âme est sans retenue I were recorded during the final months of 1997 in a Berlin park. There’s little, if anything, that would help one identify the location or date of the source material though. This proves beneficial as it strikes down any reading of the recordings as highly personal and prevents one from viewing the composition as an aural travelogue or a snapshot of a specific place and time. To be certain, this is a composition that wants us to experience sound strictly as sound. This is obvious given that the sounds Frey recorded often have a muted quality to them, resembling white noise. The brevity of the field recordings’ appearances further crystallizes their status as unglamorized material. Consider, for example, how different the piece would sound with classical instruments. The inherent emotional quality in the timbre of strings or of pressure placed upon piano keys would dramatically alter our reception of the composition. There are no overtly emotional aspects to the recordings, and this is paramount to the piece’s success. The decision to include a fading out of sound into silence is significant as it directs our ears from Frey’s field recordings to the silence he employs and then ultimately to our own surroundings. The result is a recognition of the expanded and reversed figure-ground relationship at play. Since the large majority of l’âme est sans retenue I is silence, we perceive this silence as the ground with which the sound acts upon. The presence of a “digital silence” is thus crucial as it pushes our understanding of the ground beyond what’s only present on the album to what’s also in our own listening environment. At the same time, one is hard-pressed to imagine how the alternative—an environment-sourced, Cageian non-silence—could have been utilized given the composition’s conceit. The structure of l’âme est sans retenue I fosters a relationship between the listener and the piece that is in ways both predictable and not. The amount of time that both the field recordings and silence lasts is established within the first few minutes of the piece, making the pacing of this back-and-forth quickly familiar. Since l’âme est sans retenue I is spread across five discs, one is forced to remove oneself from the piece four times if rips of the CDs weren't previously made. It's a wise move, then, to have each disc start with sound; listeners can recalibrate with the composition’s sound-silence rhythm immediately upon pressing play. The extended periods of silence, however, don't last for equal lengths of time. As such, the recognizable patterns that Frey sets up are constantly stripped away. This removal of consistency stirs a craving for the return of sound, and the fact that we as listeners are unable to foresee the precise moment it reappears makes for a lively listening experience. To be sure, one would be surprised by the reemergence of sound even if the stretches of silence were of equivalent lengths; unless one is keeping track of time, seven minutes of silence aren't particularly distinguishable from eight. Even so, it's safe to say that the varying lengths of silence subvert expectations—during the final hour, two minutes of silence are followed by one that lasts ten—and provide a much larger contrast to the other parts of the composition. The most refreshing aspect of l’âme est sans retenue I is how its structure, overall length, and field recordings are conducive to a passive engagement with it. For dozens of listens, I treated the piece as one fit for an installation. Accordingly, I would occasionally have the tracks playing on repeat throughout all 24 hours of a day. Playing on speakers in my bedroom, the field recordings' presence would often be shocking upon my return to the room—how could I forget, again, that this was still playing? But even if I had stayed in a closed-off space where the piece was playing, I would frequently forget about the piece during its long silences. This naturally led to several bouts of laughter when the sounds surfaced. But more than just being surprised and finding it all very humorous, I came to understand the field recordings as an immense source of comfort. This is undoubtedly related to the desire one has to hear something familiar (both of sounds and their internal structures) during the silent sections. Frey is conditioning the listener to become accustomed to silence during these six hours, something that is pivotal in allowing the field recordings to be so evocative. The true marvel of l’âme est sans retenue I is how we aren't necessarily moved by the sounds present within the field recordings, but by sound itself. As previously mentioned, it's the "unglamorized" nature of the field recordings (along with the structure and length of the piece) that confirms this to be Frey's intention. None of this is to say that an active engagement with l’âme est sans retenue I proves fruitless. There are numerous intriguing sounds that are contained within these field recordings. One of the most arresting segments appears at the end of disc one and the beginning of disc two—a soft but prominent gust of wind blows as chirping birds and a melodic sound akin to bells and synth pads is heard in the distance. It registers as something pensive and wistful, bringing to mind minimal ambient music such as Kazuya Nagaya's Utsuho. Near the end of disc three, the wind blows with a gale-like force. Nestled inside it, though, is a high frequency tone that provides a point of focus and consequent sense of peace in the midst of a raging storm. Subtle, striking moments such as these are scattered throughout the six hours that make up l’âme est sans retenue I. It brings to mind l’âme est sans retenue III, which was released on Radu Malfatti's b-boim label in 2008. That album contained much longer periods of sound and silence, allowing for a more readily immersive listening experience. Each segment of sound felt distinct and had something (usually a high-pitched ringing) to maintain interest. In a sense, l’âme est sans retenue III is the midpoint between Frey's weites land, tiefe zeit, räume 1-8 and l’âme est sans retenue I. The sounds contained within part one and three of l’âme est sans retenue are sourced from the same recordings, yes, but the long stretches of sound in part three almost diminish the utility of silence to that of a mere cleansing of the aural palette. There's an understanding of silence's role in terms of the piece's structure, but the length of the field recordings overwhelms the listening environment, as is the case for weites land, tiefe zeit, räume 1-8. When listening to l’âme est sans retenue I, it is impossible to ignore the meticulous structuring of material on display. As previously mentioned, the sound-silence rhythm is crucial, but it's also the sequencing of field recordings that is important. Frey makes this abundantly clear within the first few minutes of the piece. Of the first eight sections of sound, all but the third and fifth are from the same field recording session. There's a recognizable continuity that's broken by these two instances. But then Frey resumes the sound on the third segment with the ninth, and does the same for the fifth segment with the tenth. This intentional reordering discreetly enlivens the field recordings and the listening process. This juxtaposition of different sounds occurs throughout the piece, but there are also other structurally interesting decisions that Frey makes as well. Halfway into disc two, church bells can be heard and Frey decides to separate two field recordings with only a second of silence. Even so, we hear a distinct difference in the bed of sound that accompanies those bells. Near the beginning of disc four, harsh winds prevail and Frey decreases the silences here to ten seconds in order to capitalize on the ferocity of the environment. Approximately seventeen minutes into disc five, a stretch of alternating sound and silence is amusingly capped off with the sound of a ship's horn. One may not recognize all that Frey does on this record, but one can be sure that Frey has done a lot to ensure that even the ostensibly plain moments will be captivating. Granted, even the fading in and fading out of the field recordings makes the tracing of sound within each segment an enjoyable endeavor. The l’âme est sans retenue series takes its name from a book by French writer and poet Edmond Jabès. Jabès's interest in the "unwritten word" manifests in his works in various ways, one of which being pages laden with "empty" white space. His influence on Frey is clear. One is tempted to draw additional comparisons to l’âme est sans retenue—the poetry of Mallarmé, the paintings of Fontana, numerous flicker films—but none are quite satisfactory. Visual mediums necessitate an active engagement via sight, and this results in a fundamentally different experience than what one has with this specific piece by Frey. The strongest analogue that comes to mind is of wearing Molecule 01 by Escentric Molecules. Molecule 01 is a fragrance almost completely made up of the aroma chemical Iso E Super. Iso E Super is present in countless perfumes today and is used to enhance and soften notes, akin to how salt is used in cooking to draw out numerous flavors. Iso E Super has its own distinct smell—a peppery cedar with a tinge of antiseptic alcohol—but the most common result is that those smelling the chemical detect nothing at all. When perceptible, Molecule 01 is subtle and abstract (theoretically, it should amplify your skin's natural scent). One may catch a whiff of the fragrance but it will be intermittent and at varying degrees of strength. The simultaneously passive and active experience of wearing perfume and the quasi-blank nature of Molecule 01's scent provides for an experience that's extremely comparable to that of l’âme est sans retenue I. That I'm unable to think of anything else that provides a similar experience is a testament to how Frey is doing something incredibly unique here, even within the Wandelweiser camp. Frey composed the l’âme est sans retenue series from 1999-2000. As such, the first part of the series marks Erstwhile Records' first archival release. It doesn't sound the least bit dated, though, and one could easily argue that it sounds refreshing compared to all the melodic compositions that have defined Frey's recent releases. To think that this may have never seen the light of day is shocking; this is the very best piece of music that Frey has ever composed, and is an undeniably essential addition to the Wandelweiser collective's catalogue. |